Jump cut (G-4): The elimination of a strip of insignificant or unnecessary action from a continuous shot. The term also refers to a disconcerting joining of two shots that do not match in action and continuity.

David Bordwell, “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film”

What has changed in the editing styles of mainstream American cinema since the 1960s? Is continuity editing still the norm? Is continuity evolving into a more refined version of itself (intensified continuity), or is it being abandoned for something totally different (post-continuity / chaos cinema)?

Average Shot Length (ASL)

1930-1960: 8-11 seconds

1960-1980: 6-8 seconds

1980-1990: 5-7 seconds

By the 2000s: 3-6 seconds

Decline of the Establishing Shot: dropped entirely or postponed until later in the scene.

Closer Framings (especially noticeable during conversation scenes): from the medium-long shot and medium shot as the norm, to the medium close-up and close-up.

“Today, most films are cut more rapidly than at any other time in U.S. studio filmmaking. Indeed, editing rates may soon hit a wall; it’s hard to imagine a feature-length narrative movie averaging less than 1.5 seconds per shot. Has rapid cutting therefore led to a ‘post-classical’ breakdown of spatial continuity? Certainly, some action sequences are cut so fast (and staged so gracelessly) as to be incomprehensible. Nonetheless, many fast-cut sequences do remain spatially coherent…” (Bordwell, 17).

Why?

“When shots are so short, when establishing shots are brief or postponed or nonexistent, the eyelines and angles in a dialogue must be even more unambiguous, and the axis of action must be strictly respected” (Bordwell, 17).

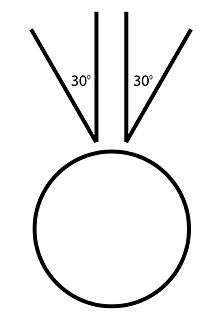

So: why do viewers remain oriented despite these rapidly accelerated cutting rates (and a general absence of establishing shots)? Bordwell’s answer is that the axis of action, eyeline match, and match-on-action cut are simply doing more work than before.

Another, alternative answer: it’s because of neuroplasticity. The flip side of us having (what appear to be, in relation to previous eras) shortened attention spans is that our brains are wired to process this new, faster style of editing. This deep shift in the nature of contemporary cognition is, in other words, an example of what philosophy calls a pharmakon, something that is both a poison and a remedy.

Katherine Hayles:

1) “hyper” attention: “switching focus rapidly among different tasks, preferring multiple information streams, seeking a high level of stimulation, and having a low tolerance for boredom”

versus

2) “deep” attention: “characterized by concentrating on a single object for long periods–say, a novel by Dickens–ignoring outside stimuli while so engaged, preferring a single information stream, and having a high tolerance for long focus times”)

A third hypothesis: the image track in contemporary cinema no longer keeps us oriented (i.e. Bordwell is wrong), but the soundtrack does…

Matthias Stork, Chaos Cinema